Peoria, Arizona

| City of Peoria | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| — City — | |||

|

|||

|

|||

| Coordinates: | |||

| Country | United States | ||

| State | Arizona | ||

| Counties | Maricopa, Yavapai | ||

| Government | |||

| - Mayor | Bob Barrett | ||

| Area | |||

| - Total | 141.7 sq mi (366.9 km2) | ||

| - Land | 138.2 sq mi (358.0 km2) | ||

| - Water | 3.5 sq mi (9.0 km2) | ||

| Elevation | 1,142 ft (348 m) | ||

| Population (2007)[1] [2] | |||

| - Total | 146,743 | ||

| - Density | 975.3/sq mi (376.7/km2) | ||

| Time zone | MST (no DST) (UTC-7) | ||

| ZIP codes | 85300-85399 | ||

| Area code(s) | 623 | ||

| FIPS code | 04-54050 | ||

| Website | http://www.peoriaaz.gov/ | ||

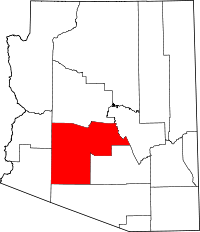

Peoria is a city in Maricopa and Yavapai counties in the U.S. state of Arizona. Located primarily in Maricopa County, it is a major suburb of Phoenix. According to 2006 Census Bureau estimates, the population of the city is 142,024.[3] Peoria is currently the fourth largest city in the state of Arizona in terms of land area, and the ninth largest city in the state in terms of population. The city was named after Peoria, Illinois. (The word “Peoria” is a corruption of the Illini word for “prairie fire.”[4][5]) Peoria is now larger in population than its namesake. It is the spring training home of the San Diego Padres and Seattle Mariners who share the Peoria Sports Complex. In July 2008, Money Magazine listed Peoria in the "Top 100 Places to Live".[6]

Contents |

History

Initial settlement

Peoria sits on flat gently sloping desert terrain in the Salt River Valley, and extends into the foothills of the mountains to the north. Like all desert towns, the key to Peoria’s settlement was water. Seasonal rainfall and runoff from mountain snowmelt filled the Salt River, at times flooding the valley with too much water and wiping out months of backbreaking labor. If the area was to become habitable and productive all year, clearly the cycle of flood and drought had to be overcome and replaced with a reliable supply of water that could be controlled year-round. The pioneers turned to irrigation. In 1868 John W. “Jack” Swilling organized a group of men to dig the first modern irrigation ditch in the Salt River Valley. Their success enticed more people to settle in the area and reap the benefits of a revitalized irrigation system.

By 1872, there were eight thousand acres (32 km²) of land under cultivation in the valley and a thriving community had been built along the Salt River. Over the years irrigation companies sprung up and in the next three years three canal systems- the Maricopa, Grand, and Salt River Valley- were constructed, each allowing sustaining growth in the Valley. Visionary settlers began to imagine the potential income to be had by reclaiming the rich desert lying higher up the slope above the recently completed Grand Canal, and in 1882 the Arizona Canal Company was organized to do just that. The proposed canal would be larger than its approximately 80,000 acres (320 km²) - including the site that would soon be Peoria- to a more consistent and regulated water system.

The Arizona Canal Company tapped William J. Murphy, a former Union Army officer, to head construction on the forty-one-mile canal. The young engineer from Illinois had just completed the grading of a stretch of the Atlantic and Pacific Railway (which later became the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe). Unable to pay Murphy in cash, the canal company offered him land and water rights to a large amount of property as compensation. With vision and foresight, he accepted and in 1885 the Arizona Canal was completed.

Murphy returned to Illinois to recruit settlers to transform the land into a sustainable farming community. Several residents of Peoria, Illinois were enticed by descriptions of the area’s climate and agricultural potential and soon purchased 5,000 acres (20 km²) among them. Four farming families left Illinois that fall to relocate to what is now Peoria. Before erecting simple adobe homes the settlers lived in large canvas tents. Peoria stood alone fourteen miles (21 km) from Phoenix, at the time a frontier city of approximately 3,500 people. An old desert frightening road connecting Phoenix to the Hassayampa River near present-day Wickenburg was the only major transportation route in the area until 1887, when a new road was laid out. This hundred foot-wide thoroughfare was named Grand Avenue, angled through the newly designed town sites of Alhambra, Glendale, and Peoria and quickly became the main route from Phoenix to Vulture Mine. The actual Peoria town site was owned by Joseph B. Greenhut and Deloss S. Brown. In 1890, the two men from Peoria, Illinois, acquired four sections of land from the government through the Desert Lands Act. They filed Peoria’s plot map with Maricopa County recorder on May 24, 1897, naming the settlement after their hometown.

The original plot map of Peoria included east and west streets (from south to north) Monroe, Madison, Jefferson, Washington, Jackson, Lincoln, Grant, and Van Buren. Streets going north and south were (from west to east) Almond (present day 85th Avenue), Peach (present day 84th Avenue), Orange (present day 83rd Avenue), Vine (present day 82nd Avenue), Walnut (present day 81st Avenue), the plot was roughly from present day Peoria and 85th Avenues to Monroe Street and 85th Avenue to Monroe Street and 81st Avenue to 81st Avenue and south of the Desert Cove alignment.

As soon as the proposed Peoria town site was surveyed a hand-dug water well was sunk in 1889 on the public right-of-way at the intersection of Grand Avenue and Washington Street. A “town well” provided water for local residents as well as the traveling public. Five years later the well was refashioned into a water tower and tank standing eighty-nine feet high. A social gathering place as well as source of water, the tower seemed to symbolize the young settlement’s growing sense of civic pride. On August 4, 1888 the Territory of Peoria, Arizona was granted a post office in its name and served a population of twenty-seven. Maricopa County supervisors defined the boundaries for School District Eleven, comprising forty-nine square miles, and the first class took place in an unoccupied brick store that faced north on Washington Street until Peoria’s first school building, a one-room structure completed in 1891. Attendance was erratic and thanks to a wagon full of nine children the district in question by county officials was saved.

Early growth of the town

Between 1891 and 1895 a spur line of the Santa, Prescott and Phoenix Railroad was placed in Peoria along with Phoenix, Glendale, Alhambra, Hesperla, and Marinette. This line helped encourage continued development of Peoria and was beneficial to the community. Peoria persuaded the rail company to build a small depot on 83rd Avenue just off Grand Avenue. This enabled area ranchers and farmers to ship their cattle and crops from the town site, as well as bring goods into the city. The depot was sold to the city of Scottsdale in 1972 where it now resides at McCormick Stillman Railroad Park.

In 1899 an atmosphere of permanence and stability for the settlement was created through the construction of the Presbyterian Church. Dedicated in 1900, the church, built in the Gothic Revival style and located at 83rd and Madison, is the oldest continuously used Presbyterian church in Arizona.

By 1917 Peoria, though still small, was slowly building into a solid commercial, agricultural, and residential location. Detracting from its growth, however, was its impermanent appearance, manifested in the tin and wood structures that had popped up around town in what was becoming known as the business district. Community leaders like J.A. Hammond and Frank Akin espoused changing the primary building material to brick since it looked better and was relatively more stable. Hammond and Akin believed that for Peoria to be acknowledged as a viable community, it had to have more substantial and attractive buildings. Due to the expense of brick it was hard to convince local business owners to invest in brick buildings. Hammond and Akins led by example, tearing down their own stores to build three new buildings that were attached and made of brick.

Fire

In July 1917, a fire broke out in a pool hall operated by E.E. Stafford, near Wilhelm’s Garage. The cause of the fire was never determined, but the fire engulfed almost the entire business district including Hammond and Akins newly constructed buildings. Glendale and Phoenix firefighters responded to the alarm, but they were too late. The damage was so severe it was as though the entire town was wiped out. Peoria was devastated. Ironically, the fire that destroyed the town’s new brick stores was incentive other business owners needed to rebuild using more sound building techniques and materials. This fire began the new era of sturdier, steadier, and more pleasing to the eye buildings. The timing of the fire was fortunate. The U.S. had just entered World War I a few months before, leading to increased production and prices around the country, especially for agricultural products. Peoria could not afford to fail to rebuild. Farmers had new money to spend, and ambitious store owners hastened to reestablish their businesses in order to take advantage of the local prosperity.

Early 20th century

Around 1919 the Peoria Chamber of Commerce formed and operated as the informal government body until Peoria’s incorporation in 1954. The Peoria volunteer fire district formed in 1920. It remained all volunteer until the mid-1950s. Peoria’s business district flourished by the early 1920s with the building of the three-story Edwards Hotel in 1918, followed by the construction of the Mabel Hood building in May 1920 at the southwest corner of Washington Street and 83rd Avenue. The John L. Meyer or “flatiron” building was completed in June 1920 and the O.O. Fuel’s Paramount Theatre in July 1920 (serving as Fire Station 1 from 1950 until 2004). The Peoria Woman’s Club House, erected in April 1918, became a center for community-wide activities. The town’s first newspaper, The Peoria Enterprise, was printed weekly beginning November 14, 1917, through April 1921.

Peoria’s first library was held at the women’s club in 1920 until it moved to the old Peoria City Hall in 1975 (where the Peoria Center for the Performing Arts was constructed and currently sits). The library eventually moved to the Peoria Municipal Complex. In May 1959 the Women’s Club gave the clubhouse to the City of Peoria where they meet free of rent.

Central School was built in 1906; the two-room masonry schoolhouse featured hardwood floors and ample storage closets surrounded by trees to shade the horses and mules. By 1910, three additional classroom buildings were built next to the central school, and in 1918 another large school building, containing an auditorium and four classrooms, was opened. In 1918 the attendance for Peoria schools was 190. Schools were set up in outlining areas in order to ease the difficulty in travel: there was the Morgan School, southwest of Peoria, with eighty-five students in 1918; Greenfield School, one mile (1.6 km) east and two miles (3 km) north of town with forty-five students; Bell School, to the northeast with thirty-nine students; and Marinette School, three miles (5 km) northwest with about twenty students.

School District Number Eleven was originally an elementary school district. Children going on to high school had to travel to Glendale High School. As the student population of Peoria grew up, the need for education above the eighth grade level became apparent. In 1919 the school board approved construction of Peoria High School. At the time many believed the three-story building designed to house the high school was too large and expensive, but when completed in 1922 had an enrollment of fifty which increased rapidly. It was built in the Spanish Mission style and featured extravagant architectural elements of Moorish Spain.

During this time, agriculture around Peoria supported a diverse amount of crops. The town was the site of four cotton gins, the main one being built at 81st and Grand Avenue in the 1923. The town also had sheep ranching, citrus farms, wheat, corn, rye, and much more.

When cotton prices fell due to the Great Depression it hit Peoria hard until a recession in 1939 due to the Second World War. The New Deal public works projects helped create jobs in Peoria including the construction of the Peoria High School gym in July 1936.

Post-war development

Increased economic activity, combined with the presence of Luke Air Force Base and tremendous growth throughout the entire Valley—coinciding with the mass-production of air conditioning in the early 1950s—led to an increase in residential housing in Peoria. A postwar construction boom set the stage for Peoria to become a suburb of Phoenix, providing housing for the capital city as growth moved west.

In 1954, Peoria was home to 1,925 residents, including an area of 720 acres (2.9 km²). The growing community's need for important services like water and sewage began to be more than the Chamber of Commerce, which served as its informal government, could provide. After much debate and skepticism Peoria incorporated on June 7, 1954. A seven member city council formed and held its first organizational meeting on June 14.

In 1955-56 a reliable house numbering system was established to help locate people more easily by street. In 1960 an outside development had major impacts on Peoria. Del Webb began to develop Sun City, which drew more residents to Peoria. By 1966 Peoria grew to encompass 3.1 square miles (8.0 km2) with 36 miles (58 km) of street. In 1968 the city passed a bond to issue securing the money to build a sewer system, which was completed in 1969. In 1970, Peoria began to transition to paid firefighting staff.

From a population of 4,792 in 1970, the city grew to 12,351 in 1980 and 50,675 in 1990. The change from 1980 to 1990 alone represented a 300 percent increase in the city’s population. In order to support its new residents or better still, keep them off the roads and working in Peoria the city turned its focus to expand its commercial and ultimately industrial development in order to maintain a balanced local economy. The Peoria Economic Development Group (PEDG) was initiated and was instrumental in bringing Peoria its first ice skating facility, modern movie theater, and “Class A” office space. Construction of the $30 million municipal complex began in 1988 at the edge of Peoria’s Old Town. The Police Department opened in 1989, the main city hall building and courts in 1991, and the library in 1993.

Spring training has a long history in Peoria. From the late 1970s to 1990, Peoria's Greenway Sports Complex served as a minor-league training facility for the Milwaukee Brewers baseball team. This small facility was located at 83rd Avenue and the Greenway Road alignment, the location of the future Peoria Sports Complex. Construction of the new complex was approved in 1990. It was completed in 1994 and was the first Major League Baseball spring training facility in the county shared by two teams. The San Diego Padres and Seattle Mariners utilize the complex year round for spring training and player development.

The city invested heavily in the sports complex and continues to subsidize its operations each year. The stadium draws many tourists, concerts, weddings, business events, boat tours, and festivals. This fuels the restaurants and hotels in the area. The stadium has helped make the 83rd Avenue and Bell/Arrowhead Fountains center area into the restaurant center of the West Valley which was estimated to have more restaurants in its quarter mile then any other in the U.S.. The stadium has more than paid for itself economically and with much of the land around it being owned by the city, selling of the land has increased city revenue and ensured the quality of the life for the area.

Current developments

Peoria continues to grow successfully. In 1999 most of the land around Lake Pleasant Regional Park was annexed into the city. Peoria has gained a world-class educational and cultural destination, the Challenger Space Center of Arizona. Also in 2007 the city completed the Peoria Center for the Performing Arts. Today most of the city’s growth is taking place in North Peoria.

The city in 2003 created a Drought Contingency Plan, and the Arizona Department of Water awarded Peoria as having Assured Water Supply, a designation that lasts until 2010. Additionally, Peoria became the first city in Arizona to use water availability rather than land mass for growth projections. In 1999 the Desert Lands Conservation Master Plan was adopted, and in May 2001 Peoria’s General Plan- the city’s blueprint for future growth and development-was approved by voters. In 2004, Peoria planners were creating a Desert Lands Conservation ordinance, which deals with hillside development, protection of native plants, and building setbacks from washes and other natural features. It provides a more comprehensive perspective when looking at development, considering the overall impact and seeking to provide the greatest amount of beneficial and conservation for both the public and the environment. Through separate development agreements, the city has managed to designate over 4,000 acres (16 km²) of mountain preserves and open space to be enjoyed by all of Peoria.

Peoria is not just working on the untouched north but moving forward with some detailed plans to help revitalize the city’s historic center. The theatre was part of the project; other proactive steps for Old Town are the creation of the Façade Renovation and an Appearance Handbook to use in renovating the area. The results of some of these efforts will be seen over the course of many years, while others very soon.

Between 1990 and 2000 Peoria was the fifth fastest growing city in the United States with a population of over 100,000, increasing in population 114 percent. In 2004 Peoria was home to over 130,000 residents spread out over 170 square miles (440 km2). Growth, however, does pay for growth. Peoria charges impact fees to developers and requires economic impact analyses on major development projects.

Peoria's identity is more related to resort and leisure living than the past, as that type of lifestyle migrates from the northeast Valley to Peoria. Peoria’s economic plan focuses on establishing the new Loop 303 freeway corridor as an industrial, commercial, mixed development use and less on traditional residential development. In July 2008 Money Magazine listed Peoria in the Top 100 Places to Live.[6]

Geography

Peoria is located at (33.582439, -112.238548).[7]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 141.7 square miles (366.9 km²), of which, 138.2 square miles (358.0 km²) of it is land and 3.5 square miles (9.0 km²) of it (2.44%) is water.

Peoria has now annexed over 170 square miles (440 km2) and is in two counties Maricopa County and Yavapai County. It is technically the largest incorporated city in Yavapai County even though almost all of Peoria’s current population resides on the Maricopa side.

The Agua Fria River and New River are the only rivers that flow through Peoria. The Agua Fria River is usually dry due to the New Waddell Dam that hold back Lake Pleasant in the northern end of the city. The New River is usually dry due to flood control measures. There are multiple washes and creeks that flow through the city as well, one of the most significant is the Skunk Creek due to its trails and connectivity with nearby Glendale.

Peoria has many smaller mountains and hills in the northern end. Some include Sunrise Mountain, West Wing Mountain, East Wing Mountain, Calderwood Butte, Cholla Mountain, White Peak, Hieroglyphic Mountains, and Twin Buttes.

The street system of Peoria is based on the city of Phoenix traditional grid system, with most roads oriented either north-south or east-west. The zero point is in downtown Phoenix at Central Avenue and Washington Street. Since Peoria is always west of zero, its north-south numbered Streets are Avenues. Major arterial streets are spaced one mile (1.6 km) apart (until you are north of roughly Pinnacle Peak Road). The one-mile (1.6 km) blocks are divided into approximately 800 house numbers although this varies. 83rd Avenue, being 8300 West. The numbers in Phoenix start at Central Avenue at a half-mile increment, going west to 7th Avenue ½ mile from Central but considered the arterial. Then the numbers go to 19th (1 mile from 7th), 27th, 35th, 43rd, 51st, 59th, 67th (in many places Peoria’s eastern border), 75th, 83rd, 91st, 99th, and so on. In northern Peoria streets are more curvilinear and begin to not follow the north-south route due to rivers, mountains, and terrain challenges. The northern end of the city does still follow the alignment theory and still has blocking according to Phoenix.

Demographics

| Historical populations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1960 | 2,593 |

|

|

| 1970 | 4,792 | 84.8% | |

| 1980 | 12,171 | 154.0% | |

| 1990 | 50,675 | 316.4% | |

| 2000 | 108,364 | 113.8% | |

As of the census[8] of 2000, there were 108,364 people, 39,184 households, and 29,309 families residing in the city. The population density was 784.0 people per square mile (302.7/km²). There were 42,573 housing units at an average density of 308.0/sq mi (118.9/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 84.95% White, 2.78% Black or African American, 0.68% Native American, 1.92% Asian, 0.11% Pacific Islander, 7.09% from other races, and 2.48% from two or more races. 15.41% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 39,184 households out of which 37.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 62.0% were married couples living together, 9.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 25.2% were non-families. 20.5% of all households were made up of individuals and 10.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.73 and the average family size was 3.16.

In the city the population was spread out with 28.4% under the age of 18, 6.7% from 18 to 24, 30.6% from 25 to 44, 19.8% from 45 to 64, and 14.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females there were 92.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $52,199, and the median income for a family was $58,388. Males had a median income of $40,448 versus $29,205 for females. The per capita income for the city was $22,726. About 3.3% of families and 5.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 5.8% of those under age 18 and 6.3% of those age 65 or over.

Government

In November 1983, Peoria citizens voted to require the direct election of the mayor and in 1989, established a city council district system that separated the city into six geographical districts, each of which elects one member of the city council. The districts are redrawn after every census. The current mayor is Bob Barrett. The current City Manager is Carl Swenson. Susan Thorpe and Susan Daluddung are the Deputy City Managers. The current Chief of Police is Larry Ratcliff and the Fire Chief is Thomas Solberg. [1]

Education

Peoria city limits lie mainly in the Peoria Unified School District, however, some portions of the northern end of the city lie within the Deer Valley Unified School District. Peoria has 4 high schools within the city limits, including:

- Peoria High School (PUSD) 1922

- Centennial High School (PUSD) 1990

- Sunrise Mountain High School (PUSD) 1996

- Liberty High School (PUSD) 2006

Some residents are districted to Peoria Unified School District that are built within Glendale city limits such as Cactus High School, Ironwood High School, and Raymond S. Kellis. Other schools that residents feed into are in the Deer Valley School District and currently effect few residents.

PUSD elementary schools within the city limits are Alta Loma, Apache, Cheyenne, Cotton Boll, Country Meadows, Coyote Hills, Desert Harbor, Frontier, Ira Murphy, Lake Pleasant, Oakwood, Oasis, Parkridge, Paseo Verde, Peoria, Santa Fe, Sky View, Sun Valley, Sundance, Vistancia and Zuni Hills. Though the city of Peoria has 21 PUSD schools some students are in the boundaries of other PUSD schools located in Glendale city limits. 10 other PUSD schools fall within Glendale city limits.

DVSD elementary schools within the city limits are Terramar and West Wing.

Additionally the city is well served by numerous publicly funded charter high schools and elementary schools.

Famous residents

- Mary Peters, former United States Secretary of Transportation.

- Ichiro Suzuki of the Seattle Mariners owns a vacation home here.

- The bands The Format, and A Change of Pace.

Sister cities

- Peoria has one sister city:[9]

![]() Borough of Ards, Northern Ireland

Borough of Ards, Northern Ireland

References

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Population for Incorporated Places in Arizona". United States Census Bureau. 2008-07-10. http://www.census.gov/popest/cities/tables/SUB-EST2007-04-04.csv. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Population for Incorporated Places over 100,000" (CSV). 2005 Population Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. June 21, 2006. http://www.census.gov/popest/cities/files/SUB-EST2005-all.csv. Retrieved November 14, 2006.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Population for All Incorporated Places in Arizona" (CSV). 2006 Population Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. http://www.census.gov/popest/cities/tables/SUB-EST2006-04-04.csv.

- ↑ "Peoria at center of 'Land of great abundance' 10/27/02". http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1N1-0F748360DC834520.html. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- ↑ "Peoria's History". http://www.peoriahistoricalsociety.org/peohistoryna.html. Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Top Places to Live". http://money.cnn.com/magazines/moneymag/bplive/2008/snapshots/PL0454050.html. Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2000 and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2005-05-03. http://www.census.gov/geo/www/gazetteer/gazette.html. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. http://factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ Sister cities designated by Sister Cities International, Inc. Retrieved on April 9, 2007.

Further reading

- More Than A Century of Peoria People, Progress,and Pride by Kathleen Gilbert

External links

- Official Government Website

- Peoria Public Library's Website

- Peoria Economic Development Department Website

- Official Tourism Website

- Peoria news, sports and things to do from The Peoria Republic newspaper

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||